AAPI History and Birthright Citizenship

By John San Nicolas | February 14, 2025

John San Nicolas is a senior at UNM studying Religious Studies and Philosophy. His research focuses on the interaction between American Christianity and politics. With family originating from Guam and Mexico, John has come to learn the importance of questioning how religion shapes and is shaped by power and politics. You can read John’s work on his Patheos.com column, “Faithful Politics,” where he addresses how Christians can build a just common life with their civic neighbors

Since taking office, President Donald J. Trump signed a slew of executive orders. These orders saturated the news cycle. Several were met with immediate legal challenges, causing concern, outrage, and even fear for many Americans. The collection of executive orders regarding immigration caught my interest.

On October 31, 2024, Trump visited Albuquerque, New Mexico for a rally. Many were surprised that Trump would visit the heart of a state that hadn’t voted red since 2004. I remember watching the live stream coverage of the rally. Throughout his hour-and-a-half-long address to his supporters, the topic that Trump hit on the most was immigration.

The Trump campaign leading up to both of his terms centered largely on immigration. For Trump, illegal immigrants are the cause of America’s woes. He cast them as violent assailants who threatened the safety and national fabric of the US, even though immigrants are by and large less likely than US-born citizens to commit crimes.

On the campaign trail, Trump falsely accused Haitian migrants of eating dogs and cats in Springfield, Ohio. Influencers in the Republican Party widely spread claims about a “gang takeover” in an apartment complex in Aurora, Colorado. Much of Trump’s rhetoric targeting immigrants resulted in real-life consequences threatening immigrant communities. We saw this before during his first term.

I set out to analyze the executive orders directed toward immigration that were signed on Day One. These orders carry the same stigmatization against immigrant communities, casting them as dangers to public health and suggesting that the US is under “invasion” by immigrants. But one order in particular stood out to me. This order is titled “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship.” In this order, Trump walks back American jurisprudence on the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees birthright citizenship. As we will see, Asian American-Pacific Islander (AAPI) history is integral to understanding how the courts have developed their interpretations of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Fourteenth Amendment

First, let us acquaint ourselves with the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment was passed by Congress in 1866 and ratified by the States in 1868.

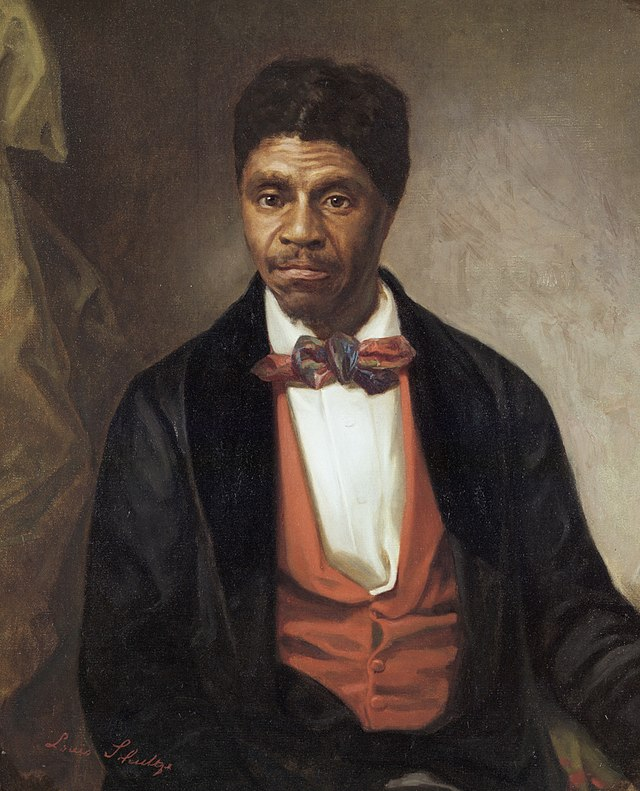

A little over a decade prior to its ratification, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) decided the Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) case. Dred and Harriet Scott were an enslaved married couple who sued for their freedom, granted that they resided in a free territory. This lawsuit spanned over the course of eleven years, with American slaveholding and anti-Blackness taking full form in the

judicial system. In Dred Scott, SCOTUS ruled that the Constitution granted citizenship to American men and women — unless they were Black. “Freedom” for Black people remained the choice of slaveowners after being denied by the highest court of the land.

Because of the intransigent nature of the judicial system, this decision was not to change any time soon. The doctrine of stare decisis holds that present judges must rule according to precedent set by past cases. As such, Justices in the U.S. Supreme Court are incredibly unlikely to roll back prior cases. For example, the nearly fifty-year gap between Roe v. Wade (1973) and Dobbs v. Jackson (2022) is quite low.

So, the ratification of amendments was the only route to correct this gravely unjust decision. Since the courts are ultimately beholden to the Constitution, only a constitutional amendment could override the Dred Scott decision. And in fact, both the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments were required to roll back the consequences of Dred Scott. The Fourteenth Amendment guarantees birthright citizenship to all who are “born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

Trump’s Attempt to Overturn the Fourteenth Amendment

In “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship,” Trump seeks to roll back the Fourteenth Amendment. It also in a serious way rewrites the history of its legal interpretation. The order reads that

the Fourteenth Amendment has never been interpreted to extend citizenship universally to everyone born within the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment has always excluded from birthright citizenship persons who were born in the United States but not “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

This claim is made without any evidence cited. When we look at the actual interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment — and we must remember that it is how SCOTUS sets precedent for this interpretation that matters, not the interpretation of a President — we find that though there are exceptions to birthright citizenship, they are fundamentally not the exceptions that Trump demands.

Before we visit the precedent on birthright citizenship, it is important to unpack this order more. Trump relies on the participial phrase, “and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” which qualifies and delimits who is eligible for birthright citizenship.

Those who the President wishes to exclude from birthright citizenship belong to one of two groups:

(1) when that person’s mother was unlawfully present in the United States and the father was not a United States citizen or lawful permanent resident at the time of said person’s birth, or (2) when that person’s mother’s presence in the United States at the time of said person’s birth was lawful but temporary (such as, but not limited to, visiting the United States under the auspices of the Visa Waiver Program or visiting on a student, work, or tourist visa) and the father was not a United States citizen or lawful permanent resident at the time of said person’s birth.

Let us see whether these exceptions to birthright citizenship have really been recognized in U.S. judicial history.

How SCOTUS Interprets the Fourteenth Amendment

Remember how Trump’s Executive Order claims that “the Fourteenth Amendment has never been interpreted to extend citizenship universally to everyone born within the United States”? This is a half truth in its plain sense. But when meant to justify the exceptions laid out in Trump’s executive order, it is an outright falsehood. The exceptions to the Fourteenth Amendment are to be determined by the Supreme Court, not by a President or any other American.

In the U.S., according to the procedures outlined in the Constitution, the implications and exceptions of constitutional amendments are to be decided by judges. And the highest level of interpretation is conducted by the highest court of the land.

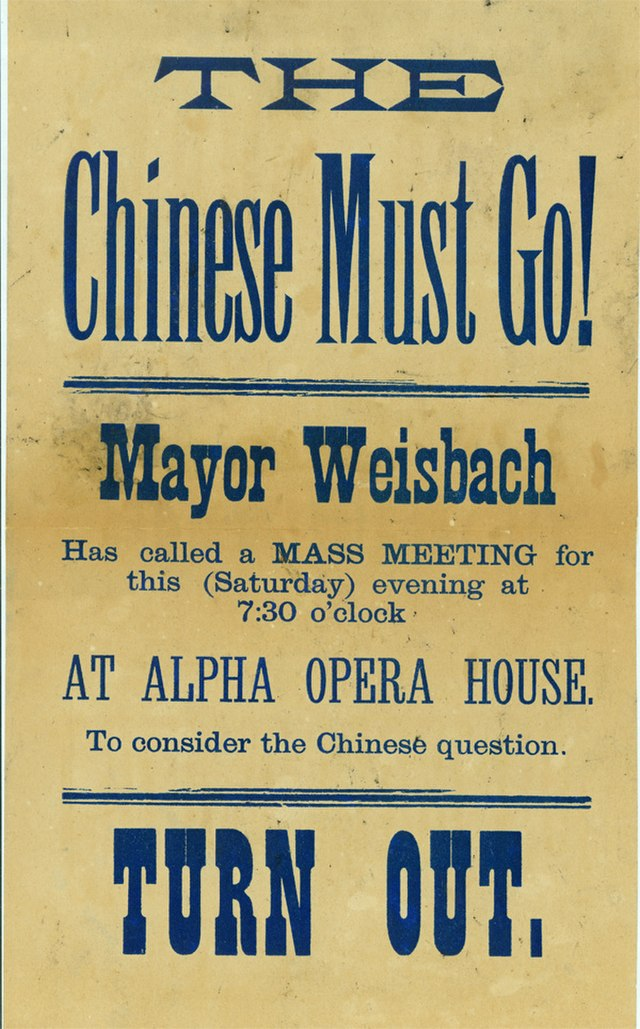

SCOTUS’s interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment is strikingly similar to the conditions which led to the Fourteenth Amendment in the first place. This time, the roles of the Court and Congress are reversed. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. Section 14 of the Act states that “no State court or court of the United States shall admit Chinese to citizenship; and all laws in conflict with this act are hereby repealed.”

This Act did not only target Chinese immigrants. It also was weaponized against their children who were born on U.S. soil. This happened to one first-generation Chinese American named Wong Kim Ark. Wong was born to immigrant parents in San Francisco, California. As an adult, he went to visit his parents in China, but upon returning to the U.S., he was informed that he was not a U.S. citizen. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which denied entry to Chinese immigrants, Ark could not return to his California home.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898) was the result when Wong challenged this in court. The Justices weighed in on an important constitutional question: does the Fourteenth Amendment guarantee birthright citizenship to all who are born on U.S. soil? Their basic answer is the same as what Trump claims in his executive order: no. But the exceptions determined by the Court are more closely specified than what the President’s order would establish.

Universal Birthright Citizenship

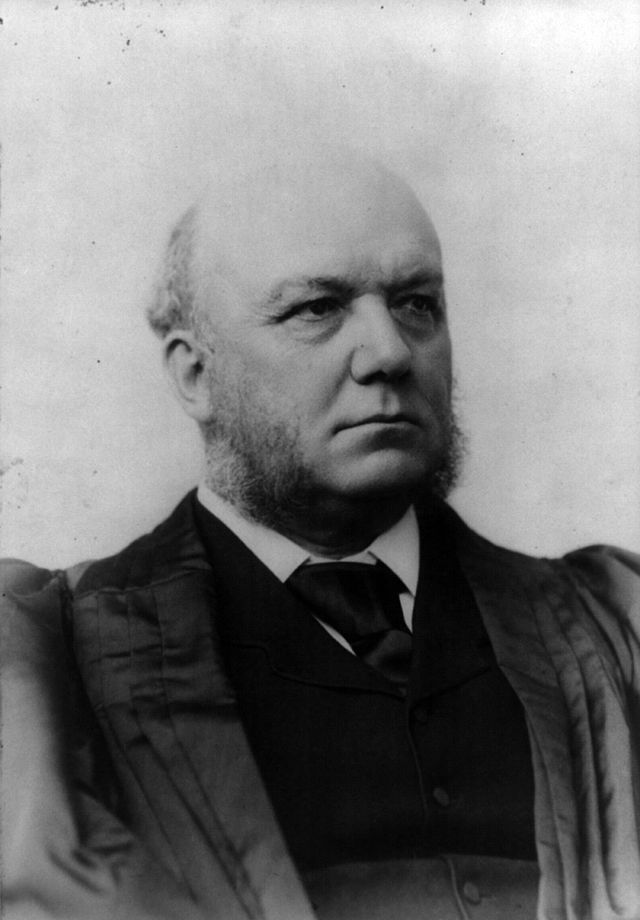

Justice Horace Gray led a 6–2 majority decision in favor of Wong. (The ninth judge, Justice Joseph McKenna, decided to sit this one out.)

In his opinion, Gray pulls not from some novel concept to protect Wong’s citizenship status, but from older European political thought. He looks to the French Revolution and their turn from jus sanguinis (rule by descent) to jus soli (rule by birth). This turn from the monarchical transfer of power from father to son, jus sanguinis, is replaced instead by rule of the people who are born in the land, jus soli; what Gray calls “birth within the dominion.”

But even for European nations like Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and Norway at the time, birthright citizenship was determined more by the status of one’s parents than by one being born “within the dominion.” Gray argues that while Europe prioritized parental descent, America prioritizes the individual being born on American soil. One finds in Gray a polemical push against what he sees as an un-American groupish and collectivist sort of thinking.

Gray puts it excellently here:

there is no authority, legislative, executive or judicial, in England or America, which maintains or intimates that the statutes (whether considered as declaratory, or as merely prospective,) conferring citizenship on foreign-born children of citizens, have superseded or restricted, in any respect, the established rule of citizenship by birth within the dominion. (Emphasis mine.)

The Exceptions

Some philosophers like to say that rules are not disproven by exceptions, but are proven to be rules by exceptions. And Gray does outline two exceptions to universal birthright citizenship.

The first exception is if a child born on U.S. soil has parents “employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China.” Of course, though Gray mentions China in particular because of the context of the case, this stands in for any foreign nation.

The second exception pertains more directly to Trump’s cornerstone: being subject to the jurisdiction of the U.S. What Gray interprets this to mean is someone who is

not merely subject in some respect or degree to the jurisdiction of the United States, but completely subject to their political jurisdiction, and owing them direct and immediate allegiance.

For Gray, this means “enemy combatants on American soil.” It also excludes certain Indigenous Americans born into sovereign nations (whom Andrew Jackson forced onto reservations through the Indian Removal Act in 1830) from birthright citizenship. This exclusion would be partially resolved by the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act guaranteeing citizenship to all Indigenous Americans. One finds a clear pattern of how restrictive U.S. citizenship has been, even against its purported intention of guaranteeing birthright citizenship to all “born within the dominion.”

I must note that Trump’s order has made many question whether he intends to include Indigenous Americans among those who are not “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” in his “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship” executive order. And there have been reports that ICE has been profiling and harassing tribal members.

Not only does his executive order implicitly revise American history; it potentially calls into question the citizenship of the First Peoples of this land.

Concluding Reflections

This executive order is incredibly concerning and dangerous. In our information-inundated age, we take for granted our immediate access to knowledge online. It is easy to look up the history of judicial interpretation of birthright citizenship. But what Trump’s executive order does is that it goes against this history of jurisprudence, essentially suggesting that his order is really in line with what Justices have ruled in the past – even though this is not the case.

That such falsehood is inscribed in an order signed by the President of the United States is bewildering. But what if this is strategic?

We saw a flurry of executive orders signed on Day One. Some of them do not make sense. Apparently, all Americans are either women or sexless since the government only recognizes people’s sex at birth (fetuses begin developing female anatomies in the early stages, but humans at conception have no sex organs of any type). And now, Trump’s citizenship order would deny birthright citizenship to babies whose parents are either temporarily or unlawfully residing in the U.S., when in fact, this has been an American practice since Wong. Justice Horace Gray would doubtlessly (polemically) see this executive order as European and groupish, not as an American championing of the individual. The Court in U.S. v. Wong based their decision on granting citizenship regardless of parents’ citizenship status!

History is a precious thing. And telling the truth about our history is of utmost importance. If I may speak theologically, history is almost liturgical; it must be habituated in our life rhythms so that we will not forget where we came from and where we fit into this orchestral score of the human story.

Not only does this order go directly against the U.S. Constitution. It obscures and undoes how SCOTUS has interpreted birthright citizenship. And Trump is taking America back to the un-American groupish view of parental juris soli that Gray saw with such disdain.

This executive order, like others, has been met with legal challenges. At the time of writing, I am learning that a third federal judge has blocked this order and nine lawsuits have been filed to stop it. It is in the nature of the American experiment to ensure that branches of government do not overstep their capacities. This system of checks and balances is under threat by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (“government efficiency” would be a nightmare for conservative anti-statists like Seymour M. Lipset!). But the American experiment is robust enough to withstand these challenges, as evidenced by the pushback against these orders.

The future of America remains to be revealed, not only in the next four years but in the extended future as well. We must continue remembering and giving life to our histories. And through our actions, we are writing the history of the now. May our history be remembered well.

Addendum: The New ColossusNot like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Written by Emma Lazarus in 1883, fifteen years before U.S. v. Wong and forty-one years before the Indian Citizenship Act was signed into law.