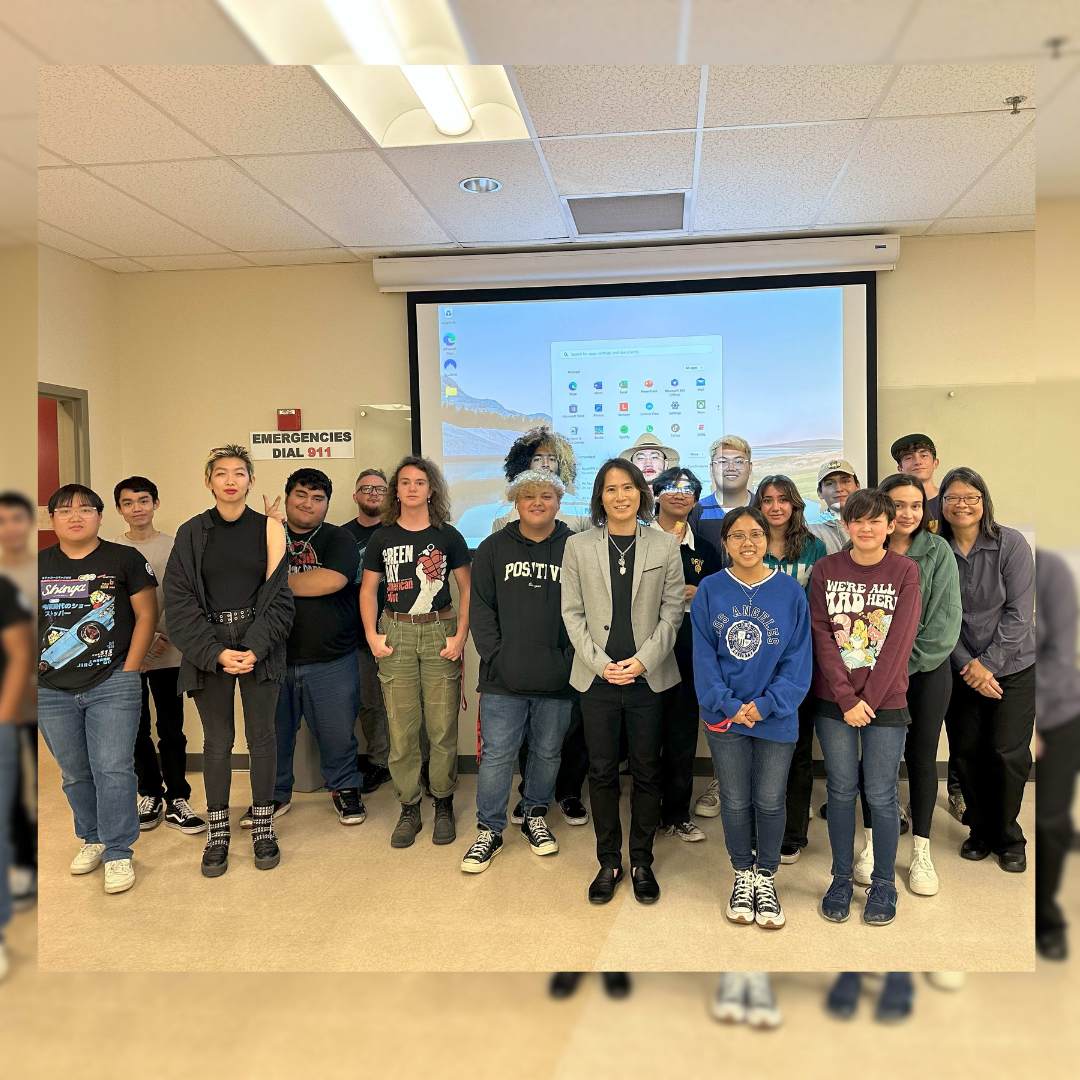

All Students Are Welcome

Office Hours: Monday - Friday 8:00am - 5:00pm

The Asian American Pacific Islander Resource Center (AAPIRC) mission is centered in fostering an educational climate of inclusiveness for all students at the University of New Mexico-Main Campus. Culturally relevant programs, leadership oppertunities, and building a sense of belonging for AAPI students are additional components of the range of engagement and services offered by AAPIRC. More information about AAPIRC is available here.